It's not entirely accurate to describe the Romantics as a band that never got its proper due. After all, they authored a song that will live for as long as there's consumer brands desperate to appear energetic and fun; and they were all over the place in 1983 behind the huge hit "Talkin in Your Sleep." Plenty of bands out there would do well to be remembered for less.

All the same, there was more to the Romantics than irresistible dance-rockers bludgeoned into oblivion in beer commercials.

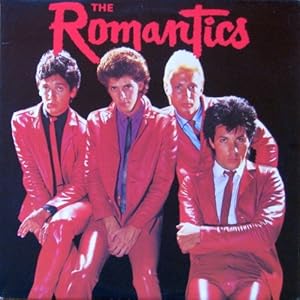

The Romantics emerged from Detroit in the late 1970s bringing a lively mix of influences: Hard-rocking Detroit garage staples like vintage Bob Seger and the MC5, and an obvious affection for British Invasion pop of the Animals, the Beatles and the Kinks. They played with energy and style, though the red-leather suits and boofy hairdos would contribute to a sense of their datedness soon enough.

Their 1979 debut album deals one splendid power popper after another, leading off with the frenetic "When I Look In Your Eyes" -- an inside-out version of "What I Like About You" with the benefit of not having been played to death. Energetic rockers "Tell It to Carrie," "Keep in Touch" and "First in Line" roar to life behind the spastic drumming of Jimmy Marinos and simple licks from guitarists Mike Skill and Wally Palmar. Ramshackle delivery was part of the charm: Palmar sung lead of most of their songs with a slight lisp.

The following album NATIONAL BREAKOUT (1980) was nearly as accomplished as the debut but didn't reach the prophecy of its title: Despite candidates like the rockabilly opener "Tomboy," it didn't produce a hit. "What I Like About You" in the meantime was ascending: Its initial release charted as high as #49 in the U.S., but then it flew to #2 in Australia, then slowly crept into rock-radio playlists, and finally went over the top accompanying Budweiser commercials. At some level I think the song's appeal is in its cheerful immediacy: There's probably quite a bit not to like about this girl who really knows how to dance, comes over whenever you call, whispers in your ear, etc., but this isn't about that. Not right now it's not.

New guitarist Coz Cansler brings a louder, harder edge to STRICTLY PERSONAL (1981), the Romantics' third album which sounds more Proto Hair Metal than Retro British Invasion. Slightly toned down and slicker, IN HEAT (1983) would be their biggest seller, producing radio/MTV hits like "Talkin in Your Sleep" and "One in a Million" along with more underexposed rockers like "Rock You Up" and a sizzling cover of Richard and the Young Lions' "Open Up Your Door."

Personnel and management issues would eventually consume the Romantics. Mike Skill departed for PERSONAL but returned as a bass player for IN HEAT. But they were never quite the same after Marinos departed following IN HEAT (the Internet suggests he had a solo/frontman career in mind but it never took off). For the Romantics it was as if Keith Moon died: The 1985 album RHYTHM ROMANCE flopped commercially and critically. Years of lawsuits followed, some chasing down revenues lost to widespread and unauthorized licensing of "What I Like About You" (according to Wikipedia the song was used to promote Budwesier, Barbie Dolls, the Los Angeles Dodgers, Papa John's, Esurance, Disney, Sea World, Toyota and T.G.I. Fridays, among others. No wonder we're all sick of it). But it wasn't their only accomplishment, if you wanna love them some more.

Thursday, January 16, 2014

Saturday, January 11, 2014

My Date with the Bee Gees

I learned something new on just about every page of David N. Meyer's new Bee Gees biography, although your mileage may vary. The Bee Gees aren't one of those bands I simply hadn't gotten around to: This was a group I'd spent most of my life purposefully avoiding.

A little context: I was in sixth grade when SATURDAY NIGHT FEVER went nuclear, though my opinion on the whole phenomenon would be expressed best by The Who, who said goodbye to "Sister Disco" and preached "Long Live Rock." This all fed a strong adolescent distaste for dancing, falsetto singing voices, music that girls liked, white satin costumes, "bands" that were really singers backed by studio pros and orchestras, on and on. It was an enduring prejudice of mine, surely injected at some level with racial and homophobic overtones, but one shared by almost all of my friends then, and many, I'd guess, still today. If nothing else, the Bee Gees of the 1970s and 1980s were awfully popular and what was cool about that?

As such they've become one of great challenges of the Desert Island Mix Tape project, and I accompanied Meyer's book by streaming the entire backcatalog of the Brothers Gibb at Rdio.

Let's begin with the book, which is deeply researched, and assertively told, mainly through revisiting contemporary accounts. The Gibbs (Barry, and his twin younger brothers Robin and Maurice) were born on the Isle of Man where their father Hugh worked as a semi-pro musician. They relocated to Manchester, then to Brisbane, Australia -- a common solution for post-war English families on the dole.

The Gibbs, Meyer writes, were delinquent middle-school drop-out pyromaniacs who otherwise were consumed by singing and encouraged -- but not overbearingly so -- by loving if insensible parents. Success as teen recording stars in Australia fed a hunger for more back in England, which came almost immediately through a fortuitous connection with manager Robert Stigwood, who had outsized ambitions of his own.

Some early Bee Gees recordings recall the Beatles, but others sound the Band, or the Kinks. Early masterpiece "To Love Somebody," Meyer writes, was the greatest Otis Redding song never performed by him. The Bee Gees wrote all their own songs (I didn't know that) and Barry emerges as a kind of brilliant craftsman in the medium of pop: He could crank out songs in almost any style, with a particular skill for capturing what was on or close to the edge of what's massively popular, carried through with wonderful three-part harmony singing ("a sound only brothers could make," as Stigwood described it).

At the same time, the Gibbs couldn't read a note of music, and, as Meyer notes, were often publically ridiculous and wrenchingly naive. Tensions emerge between alpha brother Barry and the melodramatic Robin (Maurice, the youngest, may have been the best pure musician of the three but adopted a conciliatory, "middle brother" role and didn't often engage in the ongoing competition for the spotlight between his brothers, Meyers writes). The brothers carried out these battles on the pages of the rock press with such tactless naievete it will make your hair hurt.

A reconciliation, Barry's discovery of a falsetto range, and a new producer (Arif Mardin) encouraging pursuit of a soul groove, led to 1975's groundbreaking MAIN COURSE album featuring "Jive Talkin'" and "Nights on Broadway," and it was off to the disco from there. Their tunes would provide the backbone for Stigwood's FEVER film and Barry would settle into a decade-long groove penning No. 1 singles for anyone (the Bee Gees, Kenny Rogers, Barbra Streisand, Dionne Warwick, his doomed youngest brother Andy, etc etc).

The ensuing disco backlash and their subsequent participation in Stigwood's awful "Sgt. Pepper" film (to which Meyer devotes an entire chapter) again turned the Gibbs into a kind of inconsequential, non-rock joke. At the same time they very much lived like rock stars: Robin battled an amphetamine addiction most of life; Maurice drank to excess; and Andy's taste for cocaine killed him at age 30. Barry (a pothead, but mostly high on his own gigantic ego, Meyer suggests) outlives all three of his younger siblings.

Meyer's book is loaded with strong and wildly varying opinions on the Bee Gee's music and its critical reception. Jive Talkin' is "one of the best singles ever cut" while entire albums are dismissed as "shockingly weak" (E.S.P.) or "by any reasonable standard, terrible" (High Civilization). As such the book has encountered plenty of criticism from fans, including some who have pointed out enough factual goofs to cast some doubt on Meyer's larger conclusions. In the end though, even the most ignorant haters (like, uh, adolescent me) ought to be convinced of their importance and place in rock history.

Spinning nearly the entire BeeGee catalog (more than 20 original albums not including solo Gibb records) generally reinforced the common perception that even the worst Bee Gees album can be counted on to include two or three strong pop tunes. Beyond the early standards ("New York Mining Disaster," "Massachusetts," "To Love Somebody") I was surprised at the listenability of lightly-regarded LPs like 1970's off-kilter CUCUMBER CASTLE. The sterile, "light rock" aim of the latter records make them considerably less attractive in my opinion, but they might still surprise you. I stayed alive anyway.

A little context: I was in sixth grade when SATURDAY NIGHT FEVER went nuclear, though my opinion on the whole phenomenon would be expressed best by The Who, who said goodbye to "Sister Disco" and preached "Long Live Rock." This all fed a strong adolescent distaste for dancing, falsetto singing voices, music that girls liked, white satin costumes, "bands" that were really singers backed by studio pros and orchestras, on and on. It was an enduring prejudice of mine, surely injected at some level with racial and homophobic overtones, but one shared by almost all of my friends then, and many, I'd guess, still today. If nothing else, the Bee Gees of the 1970s and 1980s were awfully popular and what was cool about that?

As such they've become one of great challenges of the Desert Island Mix Tape project, and I accompanied Meyer's book by streaming the entire backcatalog of the Brothers Gibb at Rdio.

Let's begin with the book, which is deeply researched, and assertively told, mainly through revisiting contemporary accounts. The Gibbs (Barry, and his twin younger brothers Robin and Maurice) were born on the Isle of Man where their father Hugh worked as a semi-pro musician. They relocated to Manchester, then to Brisbane, Australia -- a common solution for post-war English families on the dole.

The Gibbs, Meyer writes, were delinquent middle-school drop-out pyromaniacs who otherwise were consumed by singing and encouraged -- but not overbearingly so -- by loving if insensible parents. Success as teen recording stars in Australia fed a hunger for more back in England, which came almost immediately through a fortuitous connection with manager Robert Stigwood, who had outsized ambitions of his own.

Some early Bee Gees recordings recall the Beatles, but others sound the Band, or the Kinks. Early masterpiece "To Love Somebody," Meyer writes, was the greatest Otis Redding song never performed by him. The Bee Gees wrote all their own songs (I didn't know that) and Barry emerges as a kind of brilliant craftsman in the medium of pop: He could crank out songs in almost any style, with a particular skill for capturing what was on or close to the edge of what's massively popular, carried through with wonderful three-part harmony singing ("a sound only brothers could make," as Stigwood described it).

At the same time, the Gibbs couldn't read a note of music, and, as Meyer notes, were often publically ridiculous and wrenchingly naive. Tensions emerge between alpha brother Barry and the melodramatic Robin (Maurice, the youngest, may have been the best pure musician of the three but adopted a conciliatory, "middle brother" role and didn't often engage in the ongoing competition for the spotlight between his brothers, Meyers writes). The brothers carried out these battles on the pages of the rock press with such tactless naievete it will make your hair hurt.

A reconciliation, Barry's discovery of a falsetto range, and a new producer (Arif Mardin) encouraging pursuit of a soul groove, led to 1975's groundbreaking MAIN COURSE album featuring "Jive Talkin'" and "Nights on Broadway," and it was off to the disco from there. Their tunes would provide the backbone for Stigwood's FEVER film and Barry would settle into a decade-long groove penning No. 1 singles for anyone (the Bee Gees, Kenny Rogers, Barbra Streisand, Dionne Warwick, his doomed youngest brother Andy, etc etc).

The ensuing disco backlash and their subsequent participation in Stigwood's awful "Sgt. Pepper" film (to which Meyer devotes an entire chapter) again turned the Gibbs into a kind of inconsequential, non-rock joke. At the same time they very much lived like rock stars: Robin battled an amphetamine addiction most of life; Maurice drank to excess; and Andy's taste for cocaine killed him at age 30. Barry (a pothead, but mostly high on his own gigantic ego, Meyer suggests) outlives all three of his younger siblings.

Meyer's book is loaded with strong and wildly varying opinions on the Bee Gee's music and its critical reception. Jive Talkin' is "one of the best singles ever cut" while entire albums are dismissed as "shockingly weak" (E.S.P.) or "by any reasonable standard, terrible" (High Civilization). As such the book has encountered plenty of criticism from fans, including some who have pointed out enough factual goofs to cast some doubt on Meyer's larger conclusions. In the end though, even the most ignorant haters (like, uh, adolescent me) ought to be convinced of their importance and place in rock history.

Spinning nearly the entire BeeGee catalog (more than 20 original albums not including solo Gibb records) generally reinforced the common perception that even the worst Bee Gees album can be counted on to include two or three strong pop tunes. Beyond the early standards ("New York Mining Disaster," "Massachusetts," "To Love Somebody") I was surprised at the listenability of lightly-regarded LPs like 1970's off-kilter CUCUMBER CASTLE. The sterile, "light rock" aim of the latter records make them considerably less attractive in my opinion, but they might still surprise you. I stayed alive anyway.

Subscribe to:

Comments (Atom)